Person wearing a weighted vest eats ultra-processed food, fills out a survey, takes a nap, then gives thanks

Lifestyle Health Wrap #20

This might be my last wrap. It’s been a good run…

But it ain’t over! Hahaha. Long live Lifestyle Health.

In all seriousness, these wraps are getting old, at least for me. I need a new menu item. I’ve realize that the format is too much. I think they’re too long and, despite my efforts, I’ve struggled to make them shorter while still using the same Diet-Exercise-Sleep-Stress-Connection format.

I need to try something new. I’m not exactly sure what yet, but I’m going to retire this format for now.

So enjoy this one!

(And if you do enjoy it, there’s 19 more that came before!)

Sections

DIET | EXERCISE | SLEEP | STRESS | CONNECTION

Diet

Trends in Adults’ Intake of Un-processed/Minimally Processed, and Ultra-processed foods at Home and Away from Home in the United States from 2003–2018 | November 2, 2024 | N = 34,628 adults (aged ≥ 20 y)

Cross-Sectional

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) “is a cross-sectional, nationally representative, population-based survey designed to collect demographic, dietary intake, and health information about the non-institutionalized United States population.” (Check out the study I did using NHANES data.)

This study used the eight NHANES cohorts from 2003 to 2018 to assess what percent of the American diet tends to consist of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) and how this has changed over this period of time.

What’s an ultra-processed food? According to the NOVA classification system–which is the most widely used source for defining UPFs–and as described in this paper, UPFs are “foods that contain little or no whole foods and are highly palatable, and often include numerous ingredients and additives with cosmetic function (including emulsifiers, sweeteners, artificial flavors) of no or rare culinary use.”

Public health researchers are concerned about consumption of UPFs because they tend to be less healthy than foods that are minimally processed. This is because they tend to have high levels of fats, sodium, and sugar, and–largely because they tend to be high in those things and low in fiber–they tend to be easier to over consume. I summarized a key experiment that demonstrated that UPFs tend to be easier to over-consume (and thus gain weight from) in an earlier post. Check that out in Wrap #17.

So what did this paper find? Overall consumption of UPFs as a proportion of energy intake has increased from about 53% in 2003-2004 to about 56% in 2017-2018. Meanwhile, consumption of minimally-processed foods (i.e., whole foods: fresh fruits, vegetables, eggs, non-deli meat, etc.) has decreased from making up about 33% of energy intake to about 28.5%.

Takeaway: High consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) is generally ill-advised. Though there are some relatively healthy and nutritious foods that fall into this category–like many breads, protein products, cereals, and dairy products–generally speaking, reducing consumption of UPFs is advisable. Focusing on substituting UPFs for whole foods is likely to help prevent overeating and improve nutrition, and thereby reduce the likelihood of developing poor metabolic health.

An aside– please take my survey!

I’ve created a survey about dietary habits and opinions about using apps to track diet for a class project. It is completely anonymous and is designed to take only 4 to 5 minutes. If you can spare the time I’d greatly appreciate it!

Now back to the wrap…

Exercise

Increased weight loading reduces body weight and body fat in obese subjects – A proof of concept randomized clinical trial | April 30, 2020

N = 67 | Randomized Controlled Trial

In my opinion, the findings of this simple study are profoundly significant and have the potential to revolutionize weight-loss strategies.

This study investigated if wearing around a weighted vest was an effective weight loss method. 72 participants with mild obesity (BMI of 30-35 kg/m2) were assigned to either a high load (11% of body weight; e.g., 22 pounds for a 200 pound person) or low load (1% of body weight; e.g., 2 pounds for a 200 pound person) weighted vest group. Participants wore the weight vests for eight hours per day for three weeks.

The results of the study show that the high load treatment resulted in a more significant reduction in body weight and fat mass compared to the low load treatment. The high load group lost an average of 1.68% of their bodyweight, which was a 1.37% greater reduction in body weight than the low load group. They also lost an average of 4.82% of their fat mass, a 4.04% greater reduction in fat mass compared to the low load group.

The authors concluded that increased weight loading reduces body weight and fat mass in obese subjects, supporting the existence of a “weight loading dependent homeostatic regulation of body weight,” or “gravitostat,” in humans. Essentially, what this means is that our body adjusts its weight based on the load it carries.

Now, to be fair, there were many limitations to the study. To name a few…

The study was relatively short (3 weeks).

The measurement of weight vest usage and standing time was self-reported, which may not be accurate.

The study did not find clear mechanisms to explain the results. (Weight loss could have been a result of greater energy expenditure &/or decreased food intake; they weren’t able to determine this.)

One thing I found disappointing about this study is that there was no long-term follow-up, so it’s not clear if the weight loss was maintained.

This commentary points out a crucial aspect of the study: participants did not lose fat-free mass (FFM), in fact, there was a slight upward trend in FFM. What does this mean? First, FFM refers to the component of body weight that is not fat, about half of this is muscle mass but it also includes bone mass, organs, fluids, connective tissue, and other non-fat body components. The fact that participants didn’t lose FFM in this study is really important because this is typically not the case when people loose weight via calorie restriction or exercise.

The commentary points out that when people restrict their calorie intake or do exercise to lose weight, the reduction in FFM often leads to “adverse decline of the patients’ basal metabolic rate (which then usually favors weight regain).” So unlike calorie restriction or other exercise interventions, this new method of weight-loss from wearing a weighted best may be more sustainable, but more research is needed.

Takeaway: wearing a weighted vest may be an effective way to loose weight without losing muscle mass.

Sleep

The effects of a 20-min nap before post-lunch dip | April 1998

N = 10 | Randomized Controlled Trial

This study examined the effects of a 20-minute nap taken before the typical afternoon dip in alertness. Ten university students participated in both a nap and a no-nap condition, with a week in between.

On both days, participants' brain activity (measured using EEG), mood, task performance, and self-rated performance were measured every 20 minutes between 10 and 6 pm. On the nap day, participants took a 20-minute nap at 12:20 PM.

The study found that the nap decreased subjective sleepiness, increased self-ratings of performance, and decreased EEG alpha wave activity, which is indicative of improved alertness. Nevertheless, the nap did not improve actual cognitive task performance.1

Takeaway: The authors concluded that a 20-minute nap before the post-lunch dip can help maintain daytime alertness. These findings are not very strong due to the small sample size of 10, but many other studies since 1998 have demonstrated the benefits of an afternoon nap.

Stress

Evaluating the effects of gratitude interventions on college student well-being | May 27, 2022

N = 108 college students

Randomized Controlled Trial

This study explored the impact of different gratitude practices on the well-being of college students after 2 months of practice. “Participants ranged from 18 to 24 years old and averaged at 19 years-old (SD = 1), and primarily identified as female (73.7%; 25.6% male).” A variety of psychological measurements were taken at baseline and then 2 months later. The college student participants were divided into four groups, semi-randomly:

Free Journaling (n=40; n=27 completed the study)

“were asked to journal for 2-5 minutes each day”

Three Good Things Gratitude Journaling (n=41; n=37 completed)

“were asked to spend 2–5 min each day writing down three things they were grateful for”

Hand-Over-Heart Gratitude (n=41; n=33 completed)

“were asked to place their hand over their heart twice a day, breathe deeply, and focus for a few moments on something or someone they were grateful for”

App Prompted Hand-Over-Heart (n=10, all completed)

essentially the same as the previous group except that these participants had an app that was linked to a wristband that helped incentivized the user to practice this hand-over-heart technique in a gamified way as often as they pleased

Group assignment was semi-random because the app only worked with Android phones. So all participants with Android phones were assigned to the app group, which is why it is much smaller than the other groups (10 vs. ~40). (News flash: Androids aren’t popular in college.)

For two months, the students participated in these activities, and their well-being was assessed before and after the intervention. Measures of well-being included life satisfaction, happiness, resilience, depression, anxiety, & stress.

The study found that all three gratitude intervention groups showed improved well-being as measured by the World Health Organization-five well-being index (WHO-5) while the free journaling group did not have a significant change in well-being. In fact, there was a significant decrease in gratitude (measured by the Gratitude questionnaire GQ-6) among the free journaling group but no other significant changes in this group.

In addition to improved well-being scores, the Hand-Over-Heart group reported small to moderate decreases in negative affect, anxiety, and stress, and the Three Good Things group reported small to moderate increases in happiness and resilience, and decreases in negative affect, anxiety, and stress.

Takeaway: The authors concluded that gratitude interventions can act as simple, low-cost ways of improving well-being and reducing negative emotions for college students. And this is probably true for people who aren’t college students too.

Connection

Perceived urban environment elements associated with momentary and long-term well-being: An experience sampling method approach | February 5, 2025 | N = 273 adults (age ≥ 18) recruited in the Kashiwa-no-ha district area of the Tokyo metropolitan area | Ecological Momentary Assessment / Experience Sampling Method (ESM)

The goal of this study was to better understand how well-being, both “long-term WB (LWB), such as overall life satisfaction and (2) momentary WB (MWB), such as immediate mood” are associated with the characteristics of one’s surroundings. To do so, they used an EMA/ESM approach.

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) study method that asks participants to report on their experience “in the wild,” that is, as they go about their regular lives (that’s what the “ecological” part means). This usually involves filling out a very short survey at certain time based on some rule of the study (like the time of day or each time some event occurs) and this is often facilitated through an app. See this footnote for examples.2

Unlike most other EMA studies, in this study the researchers allowed the participants to fill out their survey whenever they felt like it. The paper doesn’t make this very clear though. They say that the method they used is an Experience Sampling Method (ESM), but they also say that ESM “can be referred to as the diary method or ecological momentary assessment.”

ESM and EMA aren’t exactly the same though. According to ExpiWell, an app company that facilitates these types of studies, “both methods gather real-time data, ESM seeks to document life as it happens … EMA aims to monitor and influence specific behaviors for research and clinical purposes.”

We asked the participants to report, using the LINE app, with the following details whenever they were experiencing various events in urban environments: MWB [momentary well being], the place where the event occurred and the characteristics of the place, whether the experience was indoor or outdoor, the time of day when the event occurred, and so on.

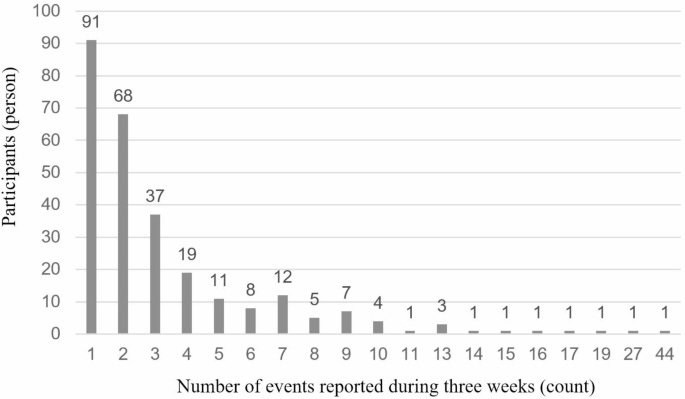

“Whenever they were experiencing various events”– nowhere else in the paper is there more detail on this point. It’s safe to assume that participants could fill out the survey at any point during the 3-week study.

What I find odd is that despite getting four reminders to fill out the survey over the course of the study, most participants only reported an experience once or twice. Meanwhile, the most active participant contributed a total of 44 of the 900 total reports. So I find these methods a bit odd.

Despite these less-than-ideal methods, the findings provide some insight into how urban environments related to momentary & long-term well-being.

Here are two excerpts from the discussion that I think sum things up well:

Urban environment elements such as cafes/restaurants/bars, cultural/sport/education facilities, public spaces, and environments perceived as natural, relaxing, and clean are positively associated with [momentary well-being]. [Momentary well-being] tends to be lower when on the move and in vibrant environments. [Long-term well-being] is positively associated with cultural/sport/education facilities, vibrancy, and communication in the urban environment.

Takeaway:

Moreover, our study suggests that creating environments that encourage easy communication, relaxation, and a connection to nature can significantly improve well-being.

Thanks for reading!

Please let me know if you notice any errors or have any feedback. If there are particular topics that you’d like to see me cover, please let me know.

Peace,

Luke

Disclaimers: This newsletter provides health information and research for educational purposes only. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Consult a healthcare professional for guidance on your health-related decisions. We are not medical professionals. The large language model Google Gemini was used to assist in the drafting of some of this content.

What were the tasks? It’s not exactly clear. This is all the detail we’re given: “computer tasks (logical reasoning, alphanumeric detection, addition, and auditory vigilance).” This is one of those uniquely short research studies that is lacking in a lot of detail. This is likely due to a word-limit constraint of the journal.

A study about mood might ask participants to fill our a survey on their phone about how they are feeling (the “assessment”) at pre-determined times (i.e., time-based EMA) throughout the day for several days. A study on addiction might ask participants to fill out a survey about drug cravings whenever they are experiencing them (i.e., event-based EMA).

I will miss reading these but look forward to what you'll do next! xo