Happy belated Thanksgiving! Thank you for following my Substack and for caring about lifestyle health.

I know Thanksgiving was two days ago and many of you are now focused on Christmas, but this wrap is going to be Thanksgiving-themed because I didn’t have the forethought of planning a Thanksgiving-themed post for last week. But it’s my favorite holiday so I’m doing it anyway. Better late than never!

As always, I hope you enjoy it and learn something.

Sections

DIET | EXERCISE | SLEEP | STRESS | CONNECTION

Diet

Thanksgiving, more than any other American holiday, is so centered around one big meal. It’s not that I actually only eat one meal on Thanksgiving day, but I know that’s what some people do and it got me thinking about the health implications of eating one meal per day as a regular thing. So I searched PubMed for “one meal per day” and found this study…

Differential Effects of One Meal per Day in the Evening on Metabolic Health and Physical Performance in Lean Individuals | January 10, 2022

https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.771944

N = 11 (5 males, 6 females, average age 31.0 ± 1.7 years1)

Randomized Crossover study

This study sought to understand whether or not there are metabolic benefits to eating once per day. They point out that most people who eat 3 times per day spend 12-16 hours in a “postprandial state.” This is the unique post-feeding physiological state in which our insulin has increased from eating and our body is mostly using glucose for energy and storing fat. They note that “from an evolutionary point of view it may be reasoned that the human body is habituated to a lower meal frequency,” meaning, our hunter-gatherer ancestors probably didn’t eat as frequently as we do and spent more time in a fasted state.

In a fasted state, our body works to conserve the storage of glucose and shifts to burning fat. “Metabolic flexibility (i.e., reciprocal changes in carbohydrate and fatty acid oxidation) is a characteristic of metabolic health and is reduced by semi-continuous feeding.” Therefore, they designed this study to investigate the effects of time-restricted feeding (TRF) “on metabolic health and physical performance in free-living healthy lean individuals compared to normal food intake (three meals per day) in a crossover design.”

In a crossover study, participants receive both “treatments” in a randomized order. In this study, the “treatments” were eating once per day in a 2-hour time window from 5 to 7 pm (evening TRF) or eating a regular three times per day. Interestingly, the participants got to choose what they ate, the only aspect of their diet that was controlled was the total amount of calories they could consume, which was kept equal for both TRF and three-meal conditions. Calorie limits were individualized for each participant based on their body size and energy expenditure. Each diet condition was adhered to for 11 days with a two-week “wash-out” period between the two conditions.

The results were pretty compelling. Here they are as summarized in the abstract:

Eucaloric meal reduction to a single meal per day lowered total body mass (3 meals/day –0.5 ± 0.3 vs. 1 meal/day –1.4 ± 0.3 kg, p = 0.03), fat mass (3 meals/day –0.1 ± 0.2 vs. 1 meal/day –0.7 ± 0.2, p = 0.049) and increased exercise fatty acid oxidation (p < 0.001) without impairment of aerobic capacity or strength (p > 0.05). Furthermore, we found lower plasma glucose concentrations during the second half of the day during the one meal per day intervention (p < 0.05).

The results strongly indicate that eating once per day can be an effective way to burn more fat from exercise (that’s the “increased exercise fatty acid oxidation” part) and manage blood sugar levels. The results weren’t dramatic, but participants only stuck to these dietary conditions for 11 days, so benefits may be greater for longer periods. Anyway, the study is well written and they cite a lot of other interesting research, so go check it out to learn more.

Exercise

My family always runs the Grand Rapids Turkey Trot on the morning of Thanksgiving. Despite the early wake-up and cold weather, it’s always a fun way to start the day and makes it feel easier to relax and over-eat the rest of the day. Getting up early for the Turkey Trot had me wondering about research on the timing of exercise, so I did some searches and found this…

Associations of timing of physical activity with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a prospective cohort study | February 18, 2023

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36546-5

N = 92,139 UK Biobank participants (average age: 62.38 ± 7.84)

Prospective Cohort Study

This study found that moderate to vigorous exercise (MVPA) “is associated with lower risks of all-cause, [cardiovascular disease] CVD, and cancer mortality regardless of the time of day” of exercise. Most notably, however, there were also statistically significant differences in disease risk based on when in the day people tended to exercise.

In particular, participants who mostly exercised during the midday-afternoon had lower risks of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality. The researchers suggest that this is likely a result of daily variations in cardiovascular reactivity (how reactive the cardiovascular system is to stress) and catecholamine reactivity (another measure of stress responsiveness2), which tend to peak in the morning and evening. The idea here is that exercising during those times of the day may take more of a toll on the body because of these pre-existing levels of heightened reactivity.

Sleep

Usually on Thanksgiving, after stuffing myself with too much food, I take a food-coma nap. This year, I didn’t do that, probably because I got enough sleep the night before getting up early for the Turkey Trot and I wasn’t as sleep-deprived as I usually am on Thanksgiving. Nevertheless, this had me wondering about the interrelationship between eating and sleep. It turns out there are a ton of different studies out there looking at post-lunch napping and the influence of eating close to bedtime. I had a hard time choosing the study for this section, but I chose the following study because of how simple it is and its large sample size.

Associations between bedtime eating or drinking, sleep duration and wake after sleep onset: findings from the American time use survey | September 13, 2021 | https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114521003597

N = 124,239 (US population sample; 53% women, 59 % 50 y.o. or younger, 69% white, non-Hispanic)

Cross-Sectional

Sleep hygiene recommendations discourage eating before bedtime; however, the impact of mealtime on sleep has been inconsistent. We examined gender-stratified associations between eating or drinking <1, <2 and <3 h before bedtime, sleep duration and wake after sleep onset (WASO >30 min).

“The American Time Use Survey (ATUS) conducted by the USA Census Bureau is an annual and cross-sectional survey in the USA” wherein “participants [are] asked to report their activities during a 24-hour period” on the day that they are called for the survey. The data used for this study came from the 2003 to 2018 respondents who reported on their weekday activities and who had nocturnal (regular; sleeping at night) sleep schedules.

The main finding was that participants who ate <1 hour before bed slept longer (35 minutes more on average for women; 25 minutes more on average for men) but were about twice as likely to experience WASO, which was defined as waking up and staying awake for at least 30 minutes during one’s “primary sleep period”. Regarding participants who didn’t eat within one hour of sleeping, they found that “as the interval of eating or drinking prior to bedtime expanded, odds of short and long sleep durations and WASO decreased.”

The authors wrote at the end of the abstract that their findings suggest that “inefficient sleep after late-night eating could increase WASO and trigger compensatory increases in sleep duration.” These results contribute evidence to the argument in favor of not eating too close to bedtime.

Stress

For some people, Thanksgiving is a stressful time when they have to interact with relatives and family who they don’t get along with. I feel lucky that it’s never been that way for me, but for those of you who do get stressed out by Thanksgiving, do you drink to compensate? This survey study investigated whether Thanksgiving Day drinking was associated with negative affect (depressed feelings, anxiety, and stress) and expectations about the holiday.

Thanksgiving Day Alcohol Use: Associations With Expectations and Negative Affect | March 11, 2019

https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294119835763

N = 208 (116 women, 92 men; average age 37.42 y.o., range = 21–75; 87.9% white)

Observational Correlational Study

This study is the first to examine Thanksgiving as a high-risk drinking event and to focus exclusively on U.S. non-college adults.

Participants were surveyed via the Amazon Mechanical Turk survey platform “one week before, one day before, and one day after Thanksgiving 2016.” This was a notable Thanksgiving considering this was the Thanksgiving right after Trump won the 2016 Presidential race (and here we are again 8 years later).

Choosing to drink on Thanksgiving day was associated with anxiety before and on Thanksgiving but it was not associated with negative affect, stress, or expectations about the holiday.

Participants who felt more anxious both before (B = 1.08, SE = .47) and on Thanksgiving (B = 1.17, SE = .47) were between 2.5× and 3.5× more likely to consume alcohol on Thanksgiving.

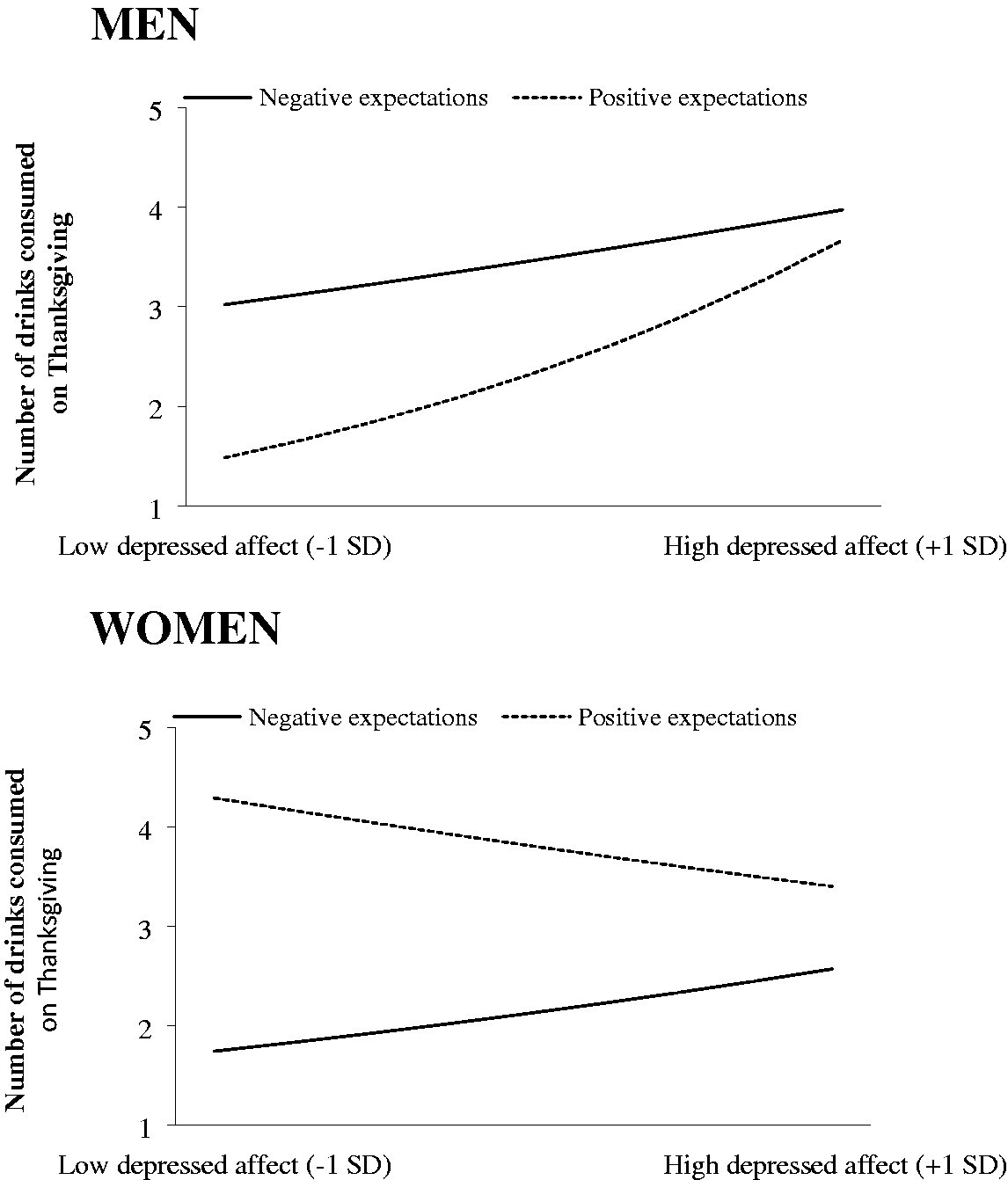

Depressed affect and expectations about the holiday had interesting differences in how they correlated the number of drinks men and women who drank on Thanksgiving had. Men with low depressed affect but negative expectations for the holiday drank more than men with low depressed affect but positive expectations. Women with low depressed affect but negative expectations for the holiday, however, drank less than women with low depressed affect but positive expectations. The number of drinks approached a similar level for both men and women with high depressed affect regardless of expectations for the holidays. These correlations are most easily understood when looking at the graphs below.

Connection

I think the most important part of Thanksgiving is social connection, which is well understood to be a very powerful predictor of health. So, on that note, here’s a study I covered in an earlier wrap that I think is worth sharing again:

Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review | July 27, 2010 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

N = 308,849 participants across 148 studies

Meta-analysis

This quote really says it all…

These findings indicate that the influence of social relationships on the risk of death are comparable with well-established risk factors for mortality such as smoking and alcohol consumption and exceed the influence of other risk factors such as physical inactivity and obesity.

But for some detail on the findings of this study, here’s the results section of the abstract:

Across 148 studies (308,849 participants), the random effects weighted average effect size was OR = 1.50 (95% CI 1.42 to 1.59), indicating a 50% increased likelihood of survival for participants with stronger social relationships. This finding remained consistent across age, sex, initial health status, cause of death, and follow-up period. Significant differences were found across the type of social measurement evaluated (p<0.001); the association was strongest for complex measures of social integration (OR = 1.91; 95% CI 1.63 to 2.23) and lowest for binary indicators of residential status (living alone versus with others) (OR = 1.19; 95% CI 0.99 to 1.44).

As a reminder, OR = odds ratio. An OR is calculated by dividing the odds of an event in one group by the odds of an event in another group3. In this case, the event of interest is survival and the exposure of interest, which defines the groups being compared, is strong vs. weak social relationships.

Because this is a meta-analysis, each of the 148 studies included used different methods, populations, and ways of defining social relationships and categorizing people into these groups. But as they say, “the finding remained consistent across age, sex, initial health status, cause of death, and follow-up period.” So this summary statistic of OR = 1.5 is pretty robust.

…

That’s all for this week!

I hope you had a nice Thanksgiving, and if you didn’t, I hope you enjoyed reading ;)

…

Disclaimer: This newsletter provides health information and research for educational purposes only. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Consult a healthcare professional for guidance on your health-related decisions. We are not medical professionals.

This second number is the standard deviation of the average age of the participants in this study.

ChatGPT explanation: “Catecholamine reactivity refers to the body’s response to stress or external stimuli in terms of the release of catecholamines, which are hormones and neurotransmitters produced by the adrenal medulla and sympathetic nervous system. The primary catecholamines involved are epinephrine (adrenaline), norepinephrine (noradrenaline), and dopamine.”

Odds = the number of cases where the event occurred DIVIDED BY the number of cases where the event of interest didn’t occur

Odds ratio = Odds from one group DIVIDED BY the odds from another group

In this case, the odds ratio of 1.5 means that people with strong social relationships had 1.5 times the odds of survival than people with weak social relationships.

great post! Thanks for the link:)