Every week, I’ll send out a list of research summaries split into the following five categories: Nutrition, Exercise, Sleep, Stress Management, and Connection1. I’ll do my best to keep things concise and rely heavily on footnotes for additional details, including explanations, citations, and definitions.

I’ll treat these categories as the tentative foundations for healthy living. I say tentative because I’m only just starting this thing, and with good reason, I could be convinced to change these categories. I’ll explain the reasoning (and lack thereof) for choosing these categories in a future post.

For now, let’s get into it…

Nutrition

Healthy Dietary Patterns with and without Meat Improved Cardiometabolic Disease Risk Factors in Adults: A Randomized Crossover Controlled Feeding Trial | DOI2 Link: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16152542 | Publication Date: Aug 3, 2024 | N3 = 41 (adults) | Method: single-blind4 randomized crossover controlled trial5

This study compared the effects of two healthy dietary patterns on cardiometabolic disease risk factors in adults classified as overweight or obese adults. One dietary pattern included lean, unprocessed beef, while the other was vegetarian. Both led to improvements in several risk factors, including cholesterol levels and blood pressure. The vegetarian diet reduced LDL, insulin, and glucose compared to the diet with beef, but those levels were not increased by the beef diet.

Overall, this study suggests that both vegetarian and omnivorous healthy dietary patterns that include lean, unprocessed beef can improve cardiometabolic health in overweight or obese adults. To learn more about why these results differ from the results of other studies suggesting that red meat is bad for cardiovascular health, I highly suggest reading into the discussion section of the article.

Exercise

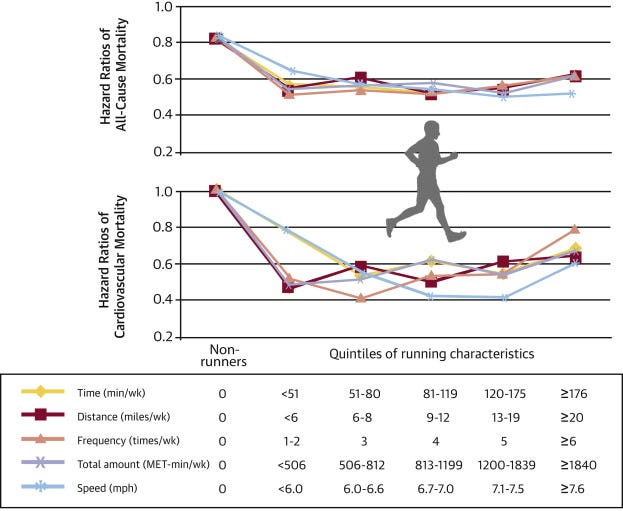

Leisure-Time Running Reduces All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality Risk | DOI Link: https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.jacc.2014.04.058 | Publication Date: Aug 5, 2014 | N = 55,137 (adults, ages 18-100) | Method: survey

"Compared with non-runners, runners had 30% and 45% lower adjusted risks of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, respectively, with a 3-year life expectancy benefit… Weekly running even <51 minutes, <6 miles, 1-2 times, <506 metabolic equivalent-minutes, or <6 mph was sufficient to reduce risk of mortality, compared with not running… Running, even 5-10 minutes per day and slow speeds <6 mph, is associated with markedly reduced risks of death from all causes and cardiovascular disease.”

Sleep

Objectively Measured Sleep Duration and Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Adults with Metabolic Syndrome: A One-Year Longitudinal Analysis of the PREDIMED-Plus Cohort | DOI Link: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16162631 | Publication Date: August 9, 2024 | N = 2119 (adults aged 55–75) | Method: cross-sectional study6

This study aimed to assess the relationship between sleep duration, including naps, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in Spanish adults7 with metabolic syndrome after one year8 of a healthy lifestyle intervention. Sleep was tracked using wrist-worn accelerometers9 and HRQoL was measured using a 36-question short-form health questionnaire (the SF-36). The findings weren’t all that exciting, but it will interesting to see how the results play out in the years to come.

What they found was that “extremes in nocturnal sleep duration,” that is less than 6 hours or more than 9 hours of sleep, correlated with lower physical health scores, and napping was “associated with higher mental component summary scores in older adults who sleep less than 7 h a night.”

These results point to a couple of things that are already generally understood: that both not enough and too much sleep are not good and that naps can have cognitive benefits.

Stress Management

Effects Of Modified Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) On The Psychological Health Of Adolescents With Subthreshold Depression: A Randomized Controlled Trial | DOI Link: https://doi.org/10.2147%2FNDT. S216401 | Publication Date: Sep. 17, 2019 | N = 56 (adolescents) | Methods: double-blind, randomized controlled trial

56 adolescents with sub-threshold depression (SD) were split into control10 and treatment groups. The treatment group received eight weeks of tailored Mindfulness-based stress reduction11 (MBSR). The effectiveness of the MBSR intervention was measured using validated mental health surveys12 before, right after, and three months after the MBSR intervention. The MBSR group showed significant decreases in depression, rumination, and increased mindfulness compared to the control group, and these effects persisted for three months.

Connection

Social support lowers cardiovascular reactivity to an acute stressor13 | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-199311000-00007 |

Published in 1993 | N = not specified in abstract | Methods: unclear, likely considered single-blind, randomized control experiment

Unlike the other studies, this article is paywalled so all I have access to is the abstract, which isn’t too jargony, so I’ve just copy-pasted it below in full. Essentially, they demonstrated something that we all probably already knew: having social support makes stuff less stressful. They demonstrate this by measuring blood pressure during a stressful experience: a speech.14

“This study examined whether social support can reduce cardiovascular reactivity to an acute stressor. College students gave a speech in one of three social conditions: alone, in the presence of a supportive confederate, or in the presence of a nonsupportive confederate.15 Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured at rest, before the speech, and during the speech. While anticipating and delivering their speech, supported and alone subjects exhibited significantly smaller increases in systolic and diastolic blood pressures than did nonsupported subjects. Supported subjects also exhibited significantly smaller increases in systolic blood pressure than did alone subjects before and during the speech. Men had higher stress-related increases in blood pressures than did women; but gender did not moderate the effects of social support on cardiovascular reactivity. These results provide experimental evidence of potential health benefits of social support during acute stressors.”

There’s a whole lot more we’ve come to understand about the health benefits of social support– similarly the social determinants of health– since 1993. I plan to delve into more of this kind of research in future posts.

Disclaimer: This newsletter provides health information and research for educational purposes only. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult a healthcare professional before making any health-related decisions. We are not medical professionals.

I hope you enjoyed this first research wrap!

Please comment with feedback and suggestions.

What did you like? What could be improved?

This category is a sort of catch-all for social connection, connection with nature, romantic/sexual connection, connection with a higher power, and/or spiritual connection. There is certainly a lot of overlap between this category and stress management, as all of these forms of connection can help with stress management, but for now, I see it as a useful distinct category. I ultimately want the things I share here to be as evidence-based as possible, so if need be I will change the categories if the best evidence suggests that I should.

What does DOI mean? Digital Object Identifier. Learn more here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_object_identifier

“N =” is customarily used as the shorthand for “this study was done with this many participants”

This means that only the investigator doesn’t know which treatment group is which when they’re looking at the data. Because it’s a dietary study, there’s not really a way of blinding the participants of their “treatment” (i.e., the diet they were prescribed for the study).

“In a [randomized] crossover trial subjects are randomly allocated to study arms where each arm consists of a sequence of two or more treatments given consecutively.” Definition from here: https://doi.org/10.1136%2Fbmj.316.7146.1719

This means that there are two or more different interventions or “treatments” and all the participants experience both (or all) of them but not everyone gets them in the same order. In this particular study, the interventions are two different diets and all the participants do both diets, but half of them get the vegetarian one first and the other half get the beef-containing one first.

To learn more about what a cross-sectional study is, here’s a source: https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/cross-sectional-study/. It’s worth noting that this study took part in the context of a much larger, randomized, interventional study, however, in this analysis, only the intervention group was surveyed. So this was essentially an observational study within an experimental study. To learn more about what an interventional study is, here’s a source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6647894

“Eligible participants were community-dwelling men (55–75 years old) and women (60–75 years old), with a body mass index (BMI) between ≥27 and <40 kg/m2 and who met at least 3 components of the MetS definition [29].”

This study is part of a much larger “6-year ongoing, multicenter, controlled, randomized intervention study … for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, involving 6874 people...” That makes this an interim analysis, meaning the research project has not been completed, but they wanted to look at the data and publish what they found after one year of the intervention.

That is something like a Fitbit or smartwatch with no functionality other than tracking movement. Call it a dumbwatch perhaps.

This just means they had neither an intervention nor a treatment given to them. That is what a control group is in most cases.

“one time per week, one hour each time group intervention”

These were the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), the Mindful Attention And Awareness Scale (MAAS), and the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS).

I found this study by using Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers by Robert Sapolsky as a desk reference. This study was mentioned in the note for page 257 in Chapter 13: Why Is Psychological Stress So Stressful?

This could really fall into the stress management section, which just goes to show the relative futility of thinking of about health in categories as opposed to holistically. Maybe I won’t stick with this format. JK, I’m sticking with it for now because it helps with the goal of covering the breadth of lifestyle health.

There have probably been 100s of studies using a very similar paradigm. One popular way of doing a study like this is by having one or two research confederates (see footnote below) in lab coats watch you and take notes during the speech. Funny enough, I took part in a study while I was an undergraduate at UChicago that used this exact method. In that study, they measured my stress response via salvary cortisol levels. Knowing about this study design from AP Psychology beforehand, I didn't feel very stressed, and remember laughing a little bit during the experience, but I’m really curious how my cortisol levels changed before and after the experience. I’m also really curious about what came of that study, but not as curious as I am about the study I participated in last year that involved watching Islamic extremist videos and fMRI, but that’s a story for another long footnote on another day.

Confederate is the term used for someone who’s involved in an experiment but isn’t a research subject. They are typically someone who works for the research lab and knows all the details of the study.